New Zealand Doesn’t Need to be Bigger. It Needs to be Clearer.

A New Year Reflection from the Quiet End of the World

By the time you read this, the holidays will be neatly folded away, the inbox will be swelling again, and the evening news will have done its best to convince you the world is coming apart at the seams. I’m writing from a farm where none of that feels quite so urgent. The grass keeps growing, children still invent games without screens, and New Zealand, despite the commentary, feels remarkably intact.

It’s a useful vantage point from which to begin the year.

Small is Not the Problem; It’s Noise

My wife Brigitte and I have been developing Sheerwater Farm on the Kaipara for thirty-four years. Long enough to plant trees that were once twigs, to raise animals across generations, and to watch families grow alongside the land. Long attention teaches you a few things: patience, humility, and the quiet confidence that some progress only reveals itself over time.

From here, the country feels less anxious than we sometimes sound. We have become very good at talking about problems. We are less practised at sitting still long enough to see what is actually working.

We’ve Perfected the Backdrop

Now it’s time to shape the foreground. New Zealand has never been at its best when trying to be big. We are far more interesting when we are being precise. Our most memorable tourism experiences are intimate, not industrial. Our strongest software companies solve very specific problems for very specific people. Our food, our design, our thinking; when they succeed, win not by volume, but by value.

We are not a volume business masquerading as a nation. That may be our greatest advantage.

In his poem New Zealand, James K. Baxter described these islands as “unshaped… on the sawyer’s bench, waiting for the chisel of the mind.” He was writing about a jagged map and a young country that had made a better world for sheep and cattle. The line still lands today, perhaps more sharply than ever. We’ve done remarkably well with the land.

The harder question now is whether we are shaping a better world for ourselves.

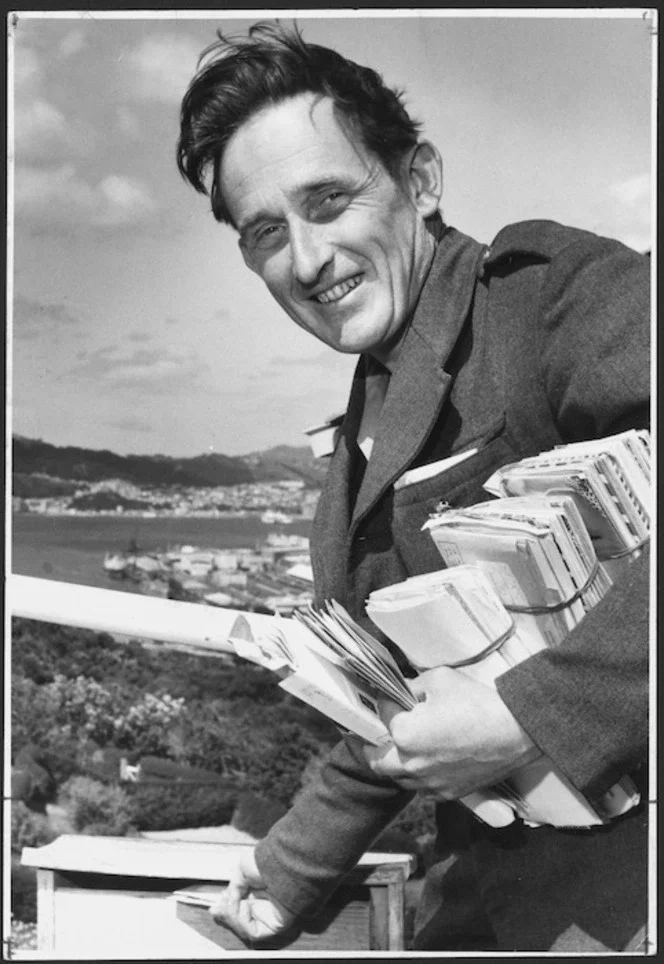

Poet and playwright James K. Baxter, one of New Zealand’s most well-known but controversial literary giants.

The World Trusts New Zealand More Than We Do

That question has long occupied our artists. Colin McCahon once said the land was ‘’not simply something to look at, but something you stood on to think’’. He understood that this place carries moral weight. It asks something of you. It is not a backdrop so much as a provocation.

Canterbury Plains (1951) by Colin McCahon, who is regarded as one of New Zealand’s most influential modern artists, particularly for his stark yet evocative landscape work.

What often goes unsaid is that the rest of the world is quietly envious of us. They envy our stability. Our cohesion—frayed at times, yes, but intact. Our ability to interact with a troubled world without being entirely consumed by it.

There is a vote of confidence extended to New Zealand almost by default. The irony is that we struggle to see it ourselves.

Why a Small Country Should Stop Apologising for Itself

And yet, for all this natural splendour, we remain oddly uncertain about our foreground. We know what we look like. We are less clear about who we are and why we are the way we are. There is no single soapbox in New Zealand—if anything, there are too many. Some delight in division. Others mistake noise for leadership and certainty for progress.

Social media, that great accelerator of opinion without reflection, has not helped. It rewards certainty, not wisdom—an awkward incentive structure for a small country trying to think its way forward.

Distance, it turns out, is not always a disadvantage. Sometimes it’s a filter.

New Zealand’s isolation in our secluded corner of the South Pacific is dramatically more palpable when viewed from space.

A Quiet Strategy for a Noisy World

If there is a task ahead, it is not to become louder or larger, but clearer. To learn how to sell less of what we have for more—more value, more meaning, more return—rather than endlessly exporting volume and wondering why the margins feel thin.

Selling more is easy. Selling better takes nerve.

This applies not only to our exports, but to how we value our own lives here—measured less in comparison and more in quality.

Returning Clearer

As work, schools, and universities come back to life, perhaps the invitation is a modest one. To return not louder, not bigger, but clearer. To remember that smallness can be a strength, precision an advantage, and optimism a discipline rather than a mood.

The sawyer’s bench is still there. The chisel hasn’t moved.

That, at least, is encouraging. As the year begins again, may we return lighter on our feet and straighter in our backs; ready, once more, to shape the foreground.

The Waimakariri River, one of the largest in Canterbury. Like the braided rivers of the South Island carving reliefs in the landscape, the chisel of the mind has the capability of reshaping the ground that we stand on.